My previous post was an introduction to the motivations and benefits of a property-based testing approach.

I also mentioned the John Hughes talk, which is great.

But there’s a catch.

Until now, we’ve been considering property-based testing in a functional way, where properties for functions depend only on the function input, assuming no state between function invocations.

But that’s not always the case, sometimes our function inserts data into some database, sends an email, or sends a message to the car anti-lock braking system.

The examples John mentions in his talk are not straightforward to solve without Erlang’s QuickCheck, since they’re verifying state machines behavior.

Since I’m a Clojurist, I was a little confused about why I couldn’t find a way to do that state machine magic using test.check, so bugging Reid and not reading the fine manual was the evident answer.

Thing is, test.check has this strategy of composing generators, particularly using bind you can generate a value based on a previously generated value by another generator.

For instance, this example shows how to generate a vector and then select an element from it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

But it doesn’t have a declarative or simple way to model expected system state.

What is state?

First thing we should think about is, when we do have state? Opposed to a situation when we’re testing a referentially transparent function.

The function sort from the previous post is referentially transparent, since for the same input vector, always return the same sorted output.

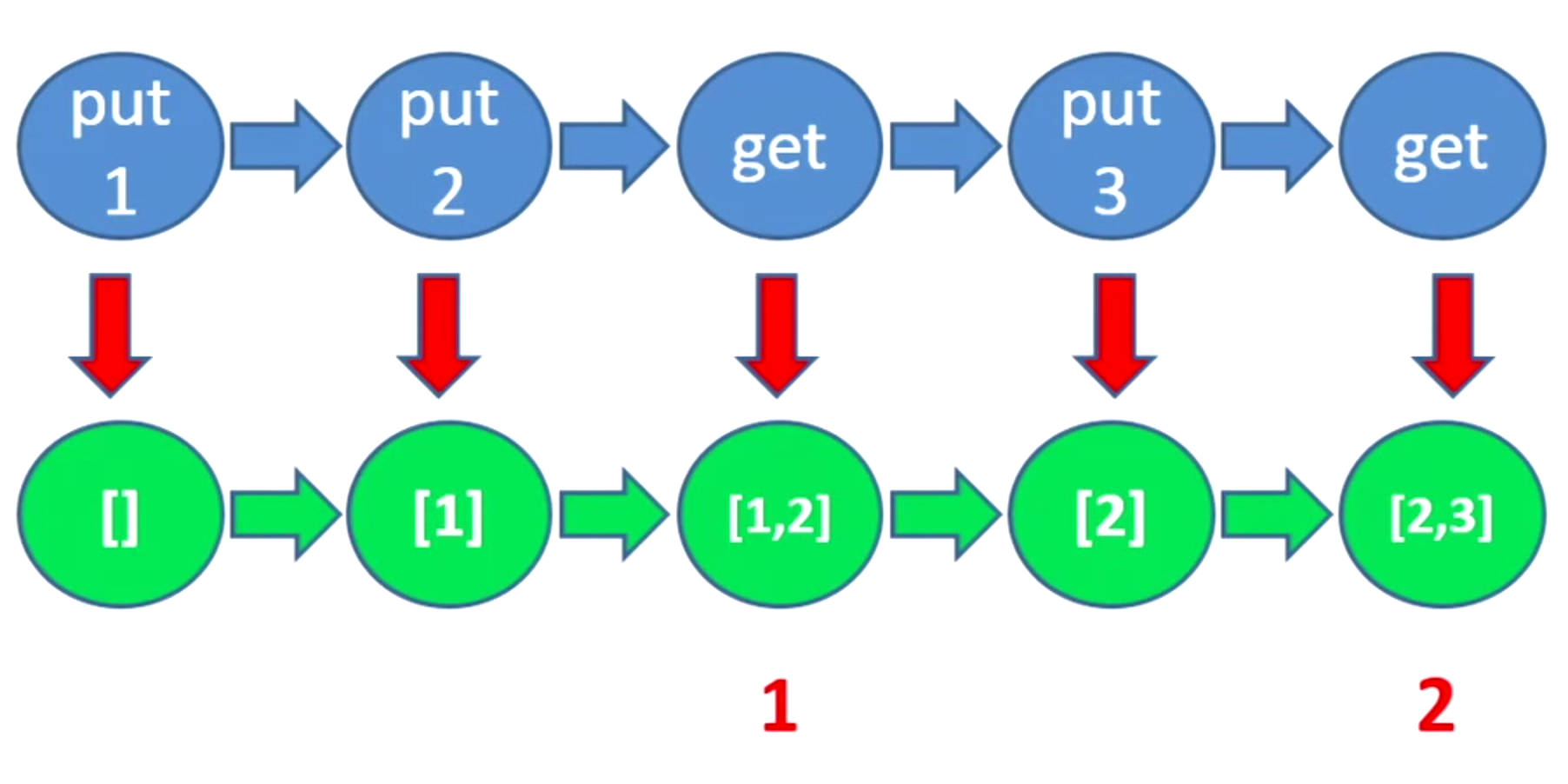

But what happens when we have a situation like the one described in the talk about this circular buffer?

If you want to test the behavior of the put and remove API calls, it depends on the state of the system, meaning what elements you already have on your buffer.

The properties put must comply with, depend on the system state.

So you have this slide from John’s presentation:

With the strategy proposed by QuickCheck to model this testing problem:

- API under test is seen as a sequence of commands.

- Model the state of the system you expect after each command execution.

- Execute the commands and validate the system state is what you expect it to be.

So we need to generate a sequence of commands and validate system state, instead of generating input for a single function.

This situation is more common than you may think, even if you’re doing functional programming state is everywhere, you have state on your databases and you also have state on your UI.

You would never think about deleting an email, and after than sending the email, that’s an invalid generated sequence of commands(relative to the “email composing state”).

This last example is exactly the one described by Ashton Kemerling from Pivotal, they’re using test.check to randomly generate test scenarios for the UI. And because test.check doesn’t have the finite state machine modeling thing, they ended up generating impossible or invalid action sequences, and having to discard them as NO-OPs when run.

FSM Behavior

The problem with Ashton’s approach for my situation, was that I had this possibly long sequence of commands or transactions, where each transaction modifies the state of the system, so the last one probable makes no sense at all without some of the in-the-middle ocurring transactions.

The problem is not only discarding invalid sequences, but how to generate something valid at all.

Say you have 3 possible actions:

- add

[id, name] - edit

[id, name] - delete

[id]

If the command sequence you generate is:

1 2 3 | |

The delete action depends on two things:

- Someone to be already added (as in the circular buffer described above).

- Selecting a valid

idfor deletion from the ones already added.

It looks like something you would do using bind, but there’s something more, there’s a state that changes when each transaction is applied, and affects each potential command that may be generated afterwards.

Searching around, I found a document titled Verifying Finite State Machine Behavior Using QuickCheck Eqc_fsm by Ida Lindgren and Robin Malmros, it’s an evaluation from Uppsala Universitet to understand whether QuickCheck is suitable for testing mobile telephone communications with base transceiver stations.

Besides the evaluation itself which is worth reading, there’s a chapter on Finite State Machines I used as guide to implement something similar with test.check.

The Command protocol

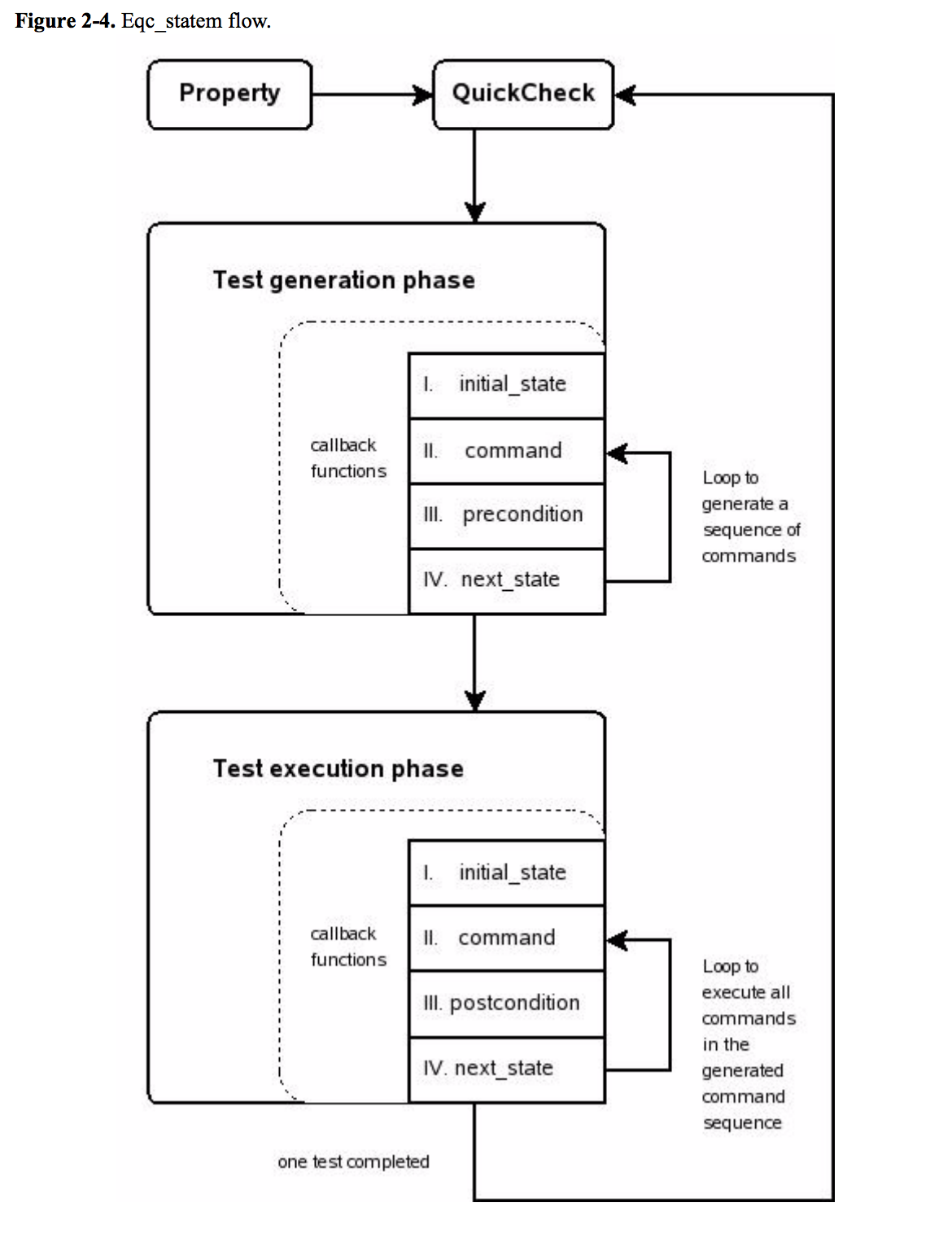

There’s a nice diagram in the paper representing the Erlang’s finite state machine flow

We observe a few things:

- You have a set of possible commands to generate.

- Each command has a precondition to check validity against current state.

- Each command affects state in some way, generating a new-state.

Translating that ideas into Clojure we can model a command protocol

1 2 3 4 | |

So far, we’ve assumed nothing about:

- How state is going to be modeled.

- What structure each generated command has.

Since we’re using test.check we need a particular protocol function generate returning the command generator.

A Command generator

Having a protocol, lets define our add, edit and delete transactions.

Questions to answer are:

- What will our model of the world look like?

- What’s the initial and expected states after applying each transaction?

Our expected state will be something like this:

1 2 3 | |

So our add transaction will be:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

The highlights:

- Our only precondition is to have a vector to

conjthe transaction into. - The

generatefunction returns a standardtest.checkgenerator for the command. - The

execfunction applies the generated command to the current system state and returns a new state.

Now, what’s interesting is the delete transaction:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Note the differences:

deletecan only be executed if the people list actually has someone inside- The generator selects to delete an

idfrom the people in the current state (usinggen/elementsselector) - Applying the command implies removing the selected person from the next state.

Valid sequence generator

So how do we generate a sequence of commands giving a command list?

This is a recursive approach, that receives the available commands and the sequence size to generate:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

The important parts being:

- Selects only one valid command to generate with

one-ofafter filtering preconditions. - If command sequence size is

0just finish, otherwise recursively concat the rest of the sequence. - The new state is updated in the step

(exec (get commands (:type cmd)) state cmd), where we need to retrieve the original command object.

If you would like to generate random sequence sizes, just bind it with gen/choose.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Note the initial state is set to {:people []} for the add command precondition to succeed.

If we generate 3 samples now, it looks good, but there’s still a problem….

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | |

Each add-cmd is repeating the id, since it’s generating it without checking the current state, let’s change our add transaction generator

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

Now the id field generator checks that the generated int doesn’t belong to the current ids in the state (we could have returned a uuid or something else, but it wouldn’t make the case for state-dependent generation)

To complete the example we need:

- To apply the commands to the system under test.

- A way to retrieve the system state.

- Comparing the final system state with our final generated expected state.

Which is pretty straightforward, so we’ll talk about shrinking first.

Shrinking the sequence

If you were to found a failing command sequence using the code above, you would quickly realize it doesn’t shrink properly.

Since we’re generating the sequence composing bind, fmap and concat and not using the internal gen/vector or gen/list generators, the generated sequence doesn’t know how to shrink itself.

If you read Reid’s account on writing test.check, there’s a glimpse of the problem we face, shrinking depends on the generated data type. So a generated int knows how to shrink itself, which is different on how a vector shrinks itself.

If you combine existing generators, you get shrinking for free, but since we’re generating our sequence recursively with concat we’ve lost the vector type shrinking capability.

And there’s a good reason it is so, but let’s first see how shrinking works in test.check.

Rose Trees

test.check complects the data generation step with the shrinking of that data. So when you generate some value, behind the scenes all the alternative shrinked scenarios are also generated.

Let’s sample an int vector generator:

1 2 | |

The sample function is hiding from you the alternatives and showing only the actual generated value.

But, if we call the generator using call-gen, we have a completely different structure:

1 2 | |

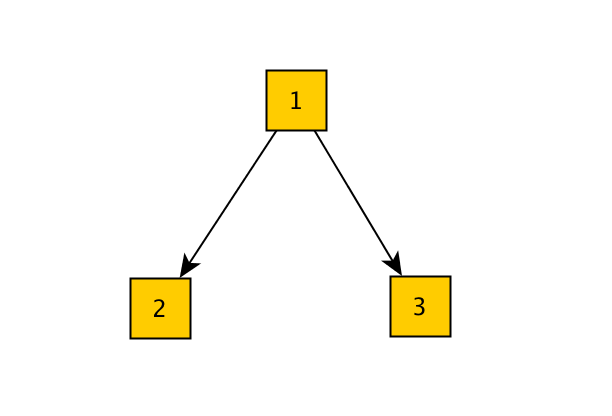

What we have is a rose tree, which is a n-ary tree, where each tree node may have any number of childs.

test.check uses a very simple modeling approach for the tree, in the form of [parent childs].

So this tree

Is represented as

1 2 | |

Everytime you get a generated value, what you’re looking at is at the root of the tree obtained with rose/root, which is exactly what gen/sample is doing.

1 2 3 4 | |

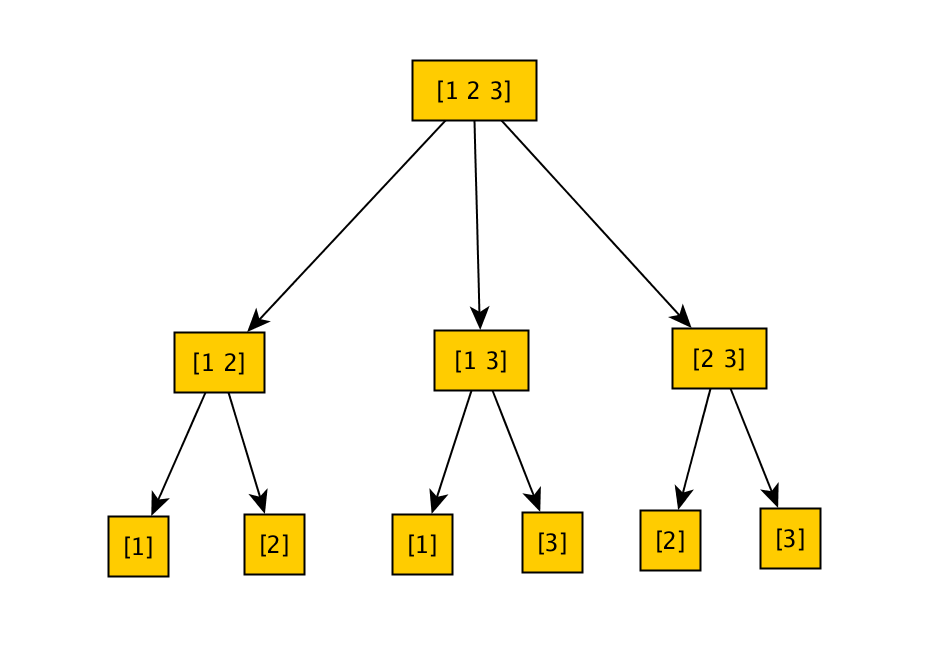

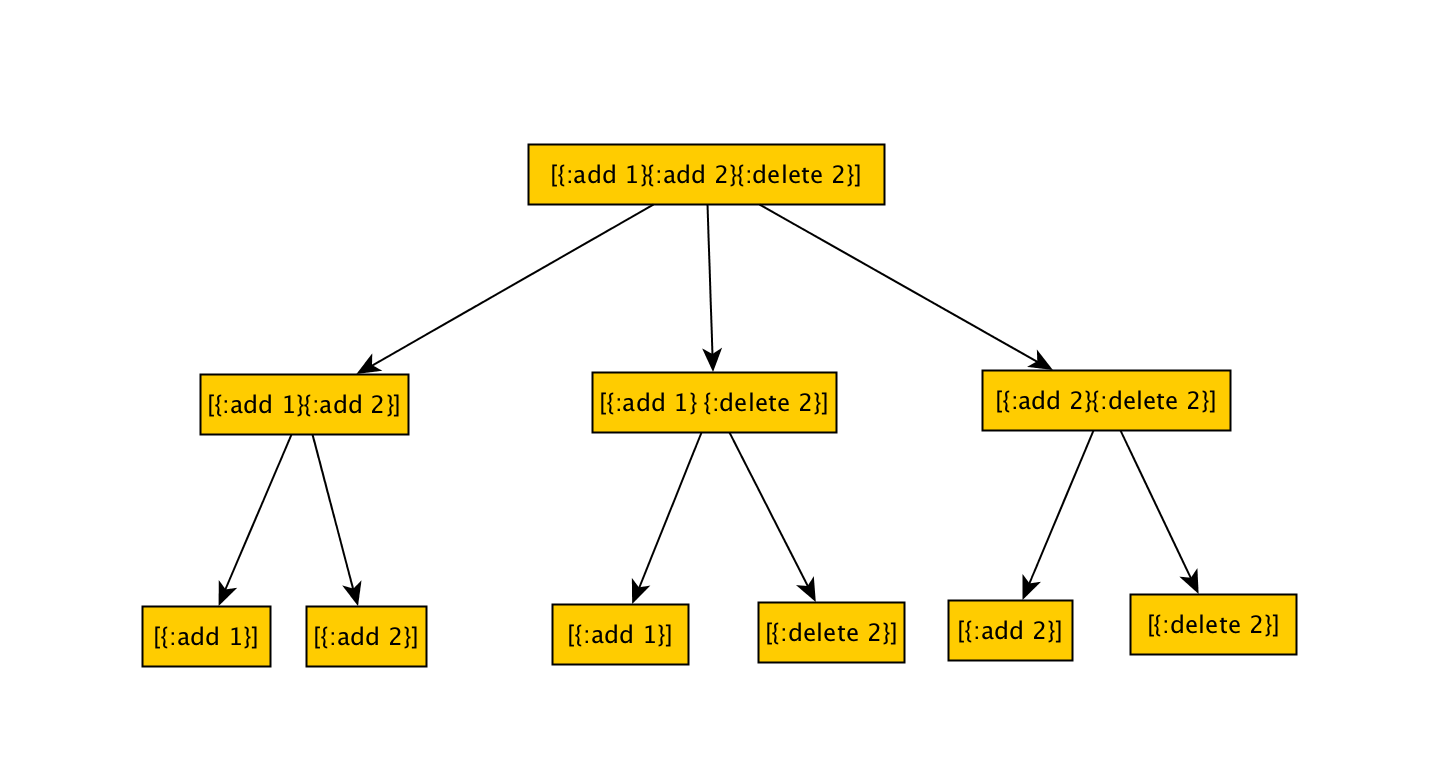

The shrinking tree you would expect for a generated vector is:

The more deep inside the tree, the more shrunk the value is. So for instance integers shrink up to zero, and vectors randomly remove elements until nothing is left.

If we were to actually look inside the shrunk vector tree, it would also include the shrunked integers, but you get the idea.

Shrinking a valid command sequence

I said before our sequence doesn’t shrink since it’s generated recursively, so this is how our sequence tree looks like so far.

But even if we were using the vector shrinker we would end up with something like this:

Since the vector shrinker doesn’t really know what a valid command sequence looks like, it will just do a random permutation of commands, ending up with many invalid sequences (like [{:add 1} {:delete 2}]).

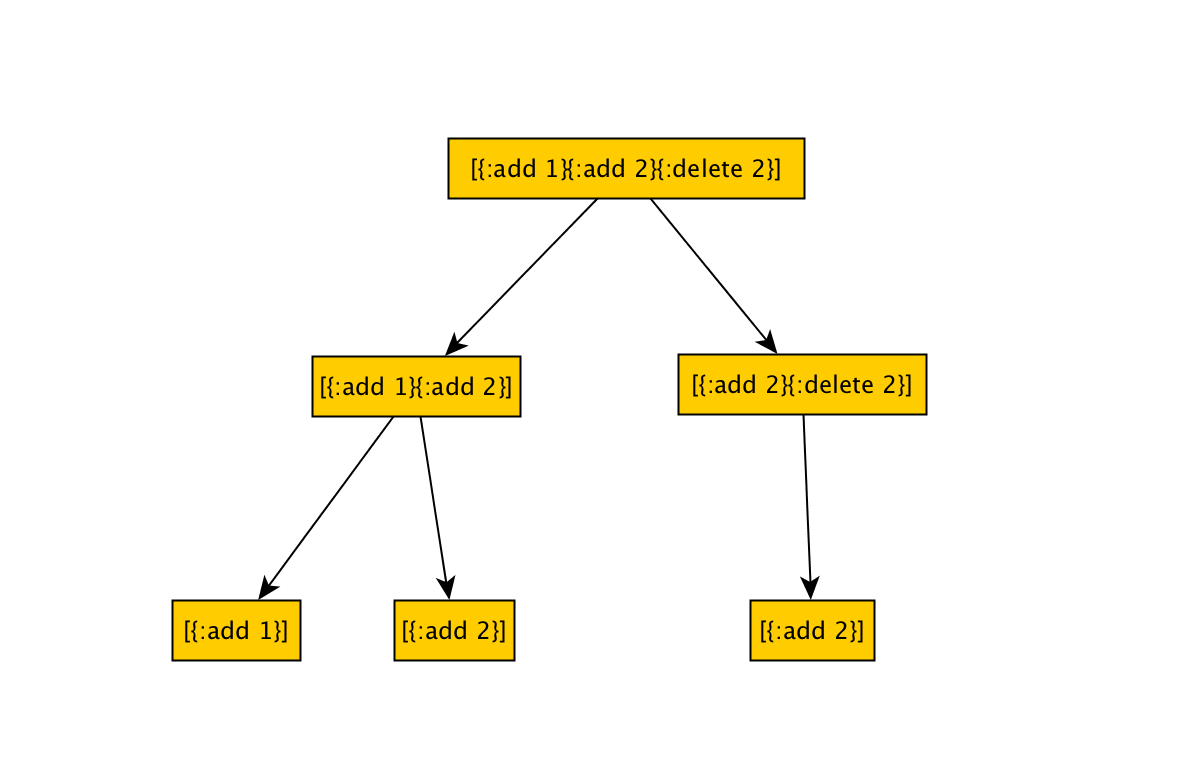

We will need a custom shrinker, that shrinks only valid command sequences, with a resulting tree like this one:

To do that, we will modify our protocol to add a new function postcondition.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

postcondition will be called while shrinking, in order to validate if a shirking sequence is valid for the hipotetical state generated by the previous commands.

Another important function is gen/pure, which allows to return our custom rose tree as generator result.

So this is how our command generator looks like now:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

We see two different things here:

- Generator also returns the state for that particular command.

- There’s a call to

shrink-sequencethat generates the rose tree given the command sequence and intermediate states.

The shrink-sequence function being:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Highlights:

- Returns a rose tree in the form

[parent childs]. remove-seqgenerates a sequence of subsequences with only one element removed.valid-sequence?usespostconditionto validate the shrinked seq.- Recursively shrinks the shrunk childs until nothing’s left.

Putting all together

I’ve put together a running sample for you to check out here.

There’s only one property defined: applying all the generated transactions should return true, but it fails when there are two delete commands present.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

If you look closely the failing test case has three add commands, but when shrunk only two needed in order to fail appear.

Have fun!

I’m guilespi on Twitter.