This is the third entry in the Decompiling Clojure series.

In the first post I showed what Clojure looks like in bytecode, and in the second post I did a quick review of the Clojure compiler and its code generation strategies.

In this post I’ll go deeper in the decompiling process.

What is decompiling?

Decompilers do not usually reconstruct the original source code, since many information meant to be read by humans (for instance comments)

is lost in the compilation process, where stuff is meant to be read only by machines, JVM bytecode in our case.

So by decompiling I mean going from lower level bytecode, to some higher level code, it doesn’t even need to be Clojure, we already know from the last post that Clojure compiler loses all macro information, so special heuristics will be needed when trying to reconstruct them.

For instance, it’s possible for let and if special forms, to be re-created using code signatures.(Think pattern matching applied to code graphs)

Decompiling goal

As I’ve said in my previous post:

What use do I have for a line based debugger with Clojure?

My goal when decompiling Clojure is not to re-create the original source code, but to re-create the AST that gave origin to the JVM bytecode I’m observing.

Since I was creating a debugger that knows about s-expressions, I needed a tree representation from the bytecode that can be properly synchronized with the Clojure source code I’m debugging.

So my decompiling goal was just getting a higher level semantic tree from the JVM bytecode.

Decompiling phases

Much of the work I’ve done was using as guide the many publications from Cristina Cifuentes, and the great book Flow Analysis of Computer Programs, which I got an used copy from Amazon. So all the smart ideas belong to them, all mistakes and nonsense are mine.

I already said I want a reasonable AST from the bytecode, so decompilation process will be split in phases

- Wind the stack and build a statement list

- Create codeblocks and a graph representing control flow

- Detect loops and nested loops

- Structure conditionals

If you want a decompiler that re-creates source code, you would add a fifth step called Emit source code.

As you smart readers would have probably noticed by now, it has some things in common with the compiling process,

only that we need to get to the AST from compiled bytecode instead of doing it from a source file,

once you have the AST you can emit whatever you want, even Basic.

1. Wind the stack

Maybe I should have used a different name for this step, since stack unwinding is usually related with C++ exception handling, and refers to how objects allocated are destroyed when exiting the function and destroying the frame.

But in the general case, stack unwind refers to what happens with the stack when a function is finished and the current frame needs to be cleared.

And if we go to the dictionary - pun intended -

to become uncoiled or disentangled

I’m happy to say we will coil the uncoiled stack into proper statements.

As we saw in the second post of our series, the JVM uses a stack based approach to parameter passing

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

So our first step is about getting the stack back together.

Some statements are going to be quite similar to what the Clojure compiler already recognizes, such as IfExpr representing an if conditional, but many statements at this stage won’t have a direct mapping in Clojure, for instance the AssignStatement representing an assignment to a variable, does not exist in the Clojure compiler, and higher level constructs such as LetFnExpr or MapExpr won’t be mapped at this stage of low-level bytecode.

So a reduced list would look like:

- AssignStatatement

- IfStatement

- InvokeStatement

- ReturnStatement

- NewStatement

So we’re dealing with less typed expressions/statements, just a small set of generic control structures.

One important thing when winding the stack is: in many cases statement compose, for instance an InvokeStatement result may be used directly from the stack into a subsequent IfStatement.

Let me show you.

Getting back to our previous example

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Decompiled as

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Lines 0 and 1 are responsible for the (inc 1) part of the code, decompiling to clojure.lang.Numbers.inc(1), which result is directly used in line 7 which compares with the long value 2 pushed on line 4.

So our first decompiled statement on line 0 is an IfStatement, which contains the InvokeStatement inside.

1 2 3 | |

When this step is finished all the low level concepts will be removed, and high level concepts were re-introduced, such as parameter passing.

But we’re still stuck with our damn Basic!

Codeblock Graph

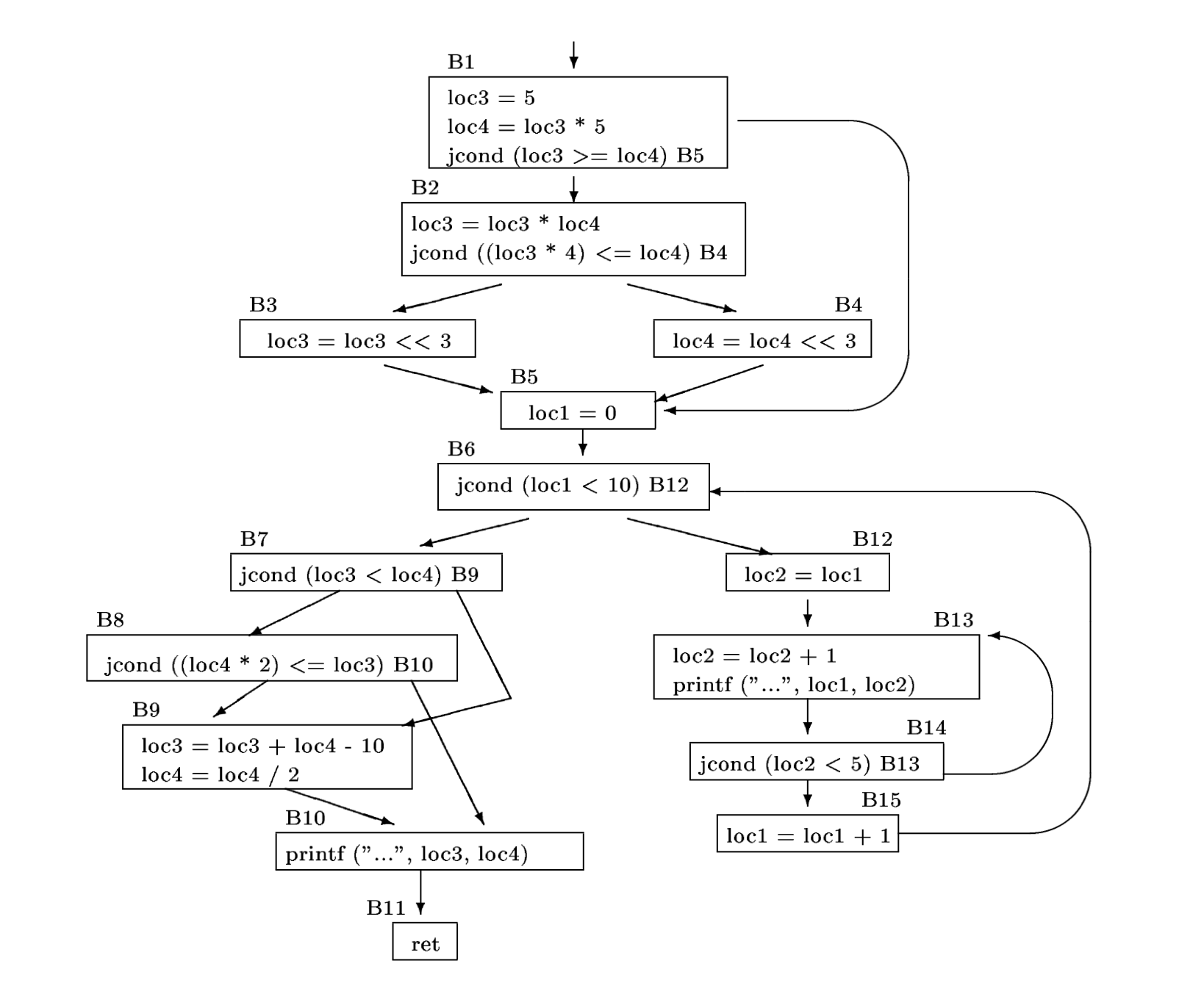

A Codeblock is a sequence of statements with no branch statements in the middle, meaning execution starts at the first statement, and ends with the last one.

The following is a control flow graph, with code blocks numbered from B1 to B15.

Note we’re building a graph here, not a tree.

A tree is a minimally connected graph, having only one path between any two vertices,

when modeling control flow you can have many paths between two vertices,

for instance in our example B1->B2->B4->B5 and B1->B5.

This is the first step of the control flow analysis phase, having identified the basic branching statements from the previous step, building the graph is straightforward.

Loop Detection

Loop detection is one of the most difficult tasks when writing a decompiler.

Main reason is when you’re reading bytecode or assembly, you’re not entirely sure about the compiler used to generate that, you may be trying to decompile bytecode written by hand, which may never map to a known higher level construct.

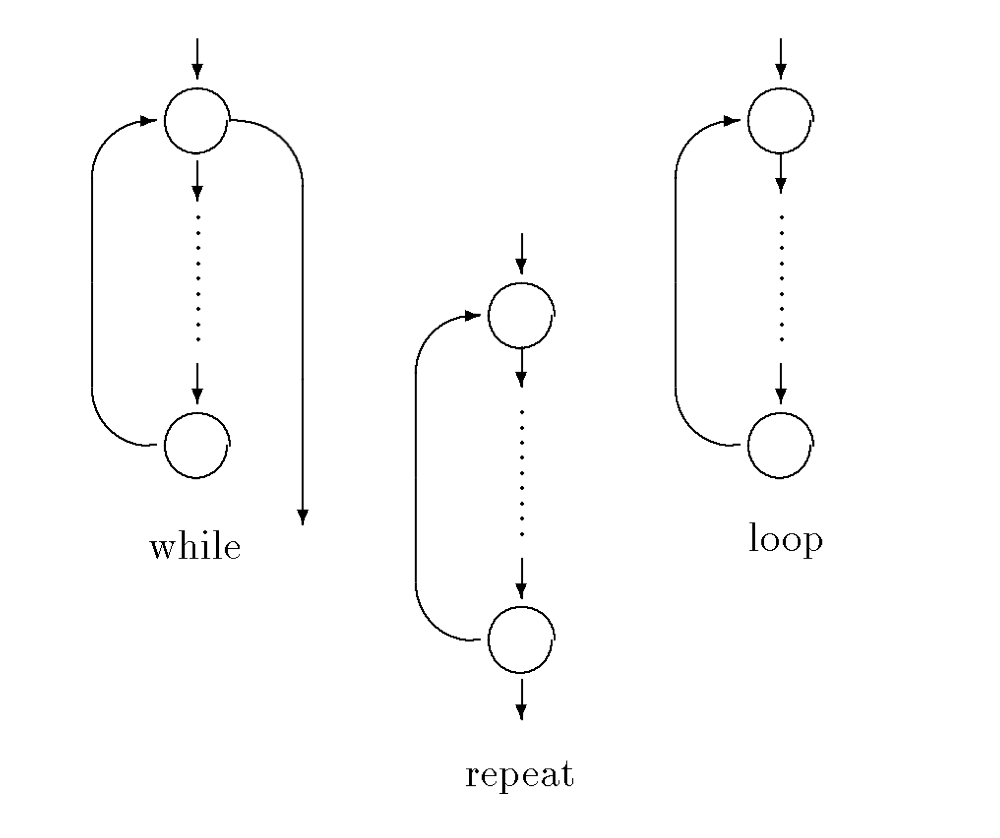

For instance, there are a few higher level constructs identified with loops, which usually take the following form:

But then you may have a graph with the following improper looping structures:

Improper loops ranging from multi-entry or multi-exit, something you can find on goto enabled languages, to parallel loops with a common header node, or entwined loops.

In our case, we can assume all bytecode we’re going to find is always created from a reasonable Clojure compiler,

and we can safely guess goto support won’t be approved by Rich Hickey any time soon.

So, a loop needs to be defined in terms of the graph representation, which not only determines the extent of the loop but also the nesting of the different loops in the function being decompiled.

The loop detection algorithms I used were taken directly from Cifuentes papers about decompiling, which in turn took the ideas from James F.Allen and John Cocke of using graph interval theory for flow analysis, since it satisfies the necessary conditions for loops:

- One loop per interval

- A nesting order is provided by the derived sequence of graphs.

Even if we don’t have improper loops, we need to know which IfStatements correspond to a loop header before assuming it’s indeed an If.

So, what does a Clojure loop looks like?

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Our first phase decompiler would see it as:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Well, we had a GOTO after all… as you see a loop is just an If statement followed by a backlink, in this case solved with a GOTO branching statement.

Now if I leave the debug comments from my decompiler, you’ll see a couple extra things:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

- Code blocks are identified

- Loop belonging nodes are identified

- Loop header and latch nodes are also identified

Structuring Conditionals

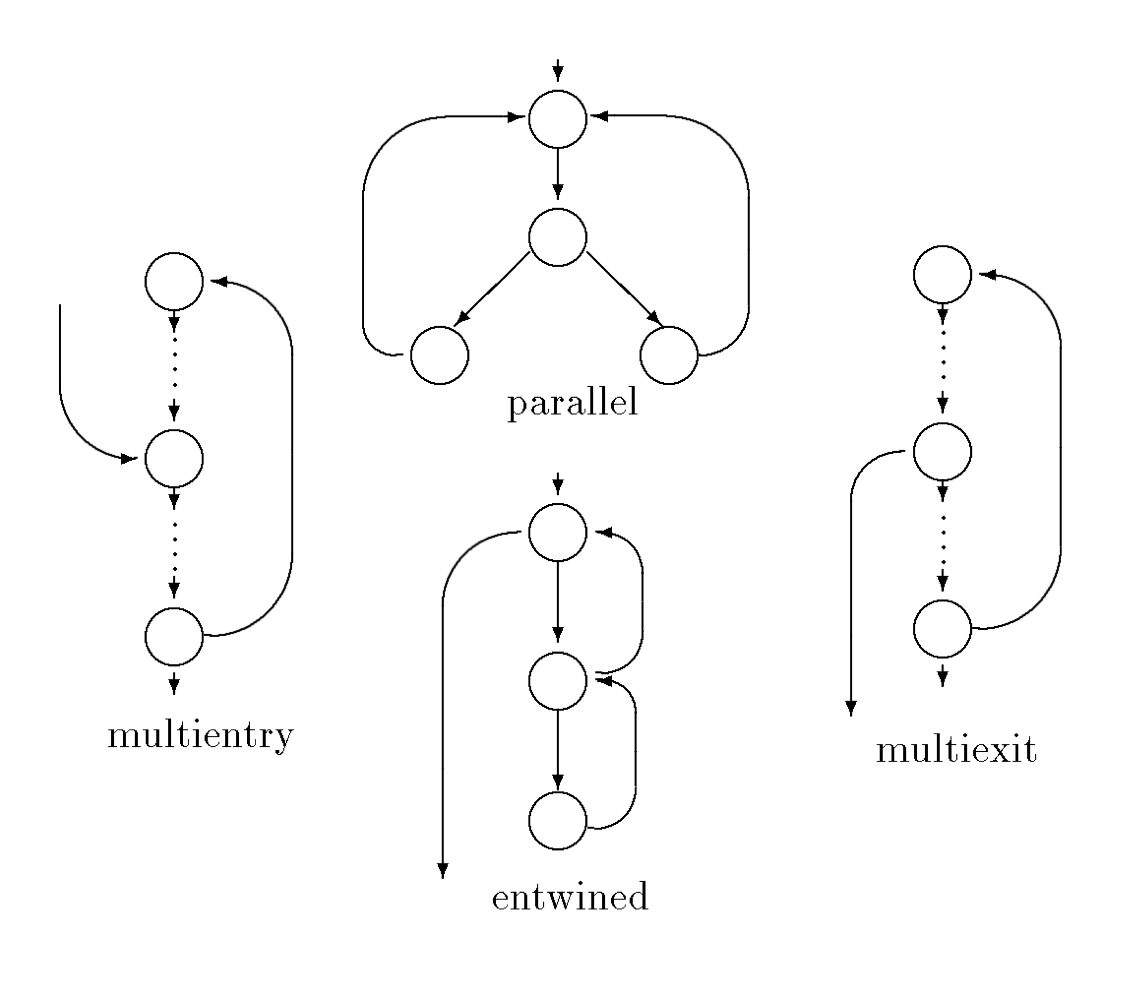

Conditionals refer to if, when, case and other conditionals that may be found in code, which are usually 1-way or 2-way conditioned branches,

all of them have a common end node reached by all paths.

Since Clojure when is a macro expanding to an if, it’s just the 1-way conditional branch, if the if clause has an else part we’re in the 2-way conditional branch, where the else part is taken before reaching the common follow node.

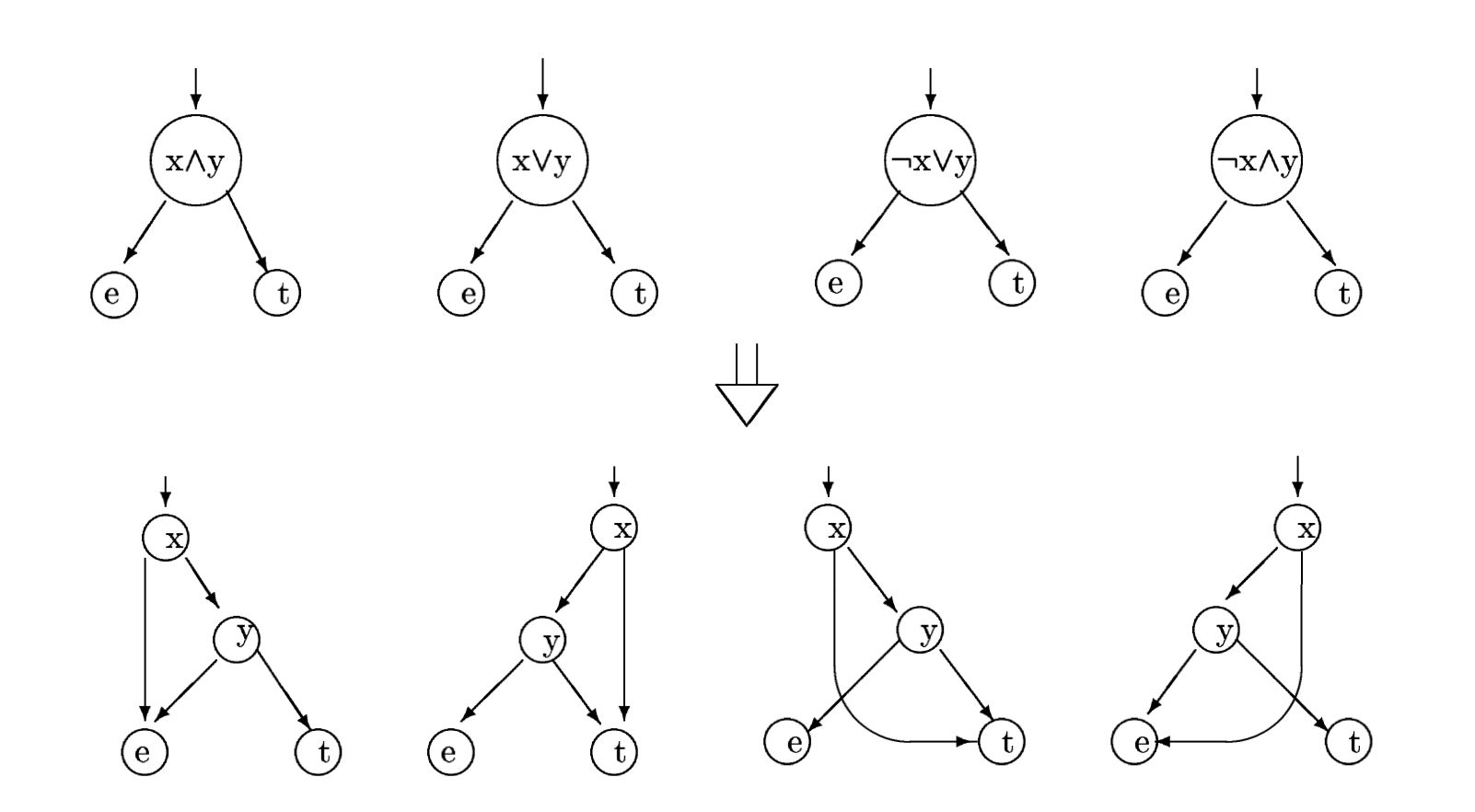

The more difficult situation arises when trying to structure compound boolean conditions, as you see in the following picture:

You should expect different IfStatements one behind the other, all being part of the same higher-level compound conditional which is compiled in a short-circuit fashion,

with two chained if statements.

With Clojure we have an additional problem, for instance the following example:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Decompiles to the following Basic:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Wait a minute!!

We should be seeing only two IfStatements there, one for each part of the compound conditional, but there are three, what’s going on?

As you see on line 21 the same condition of line 8 is being tested again, which we already know it’s false, why someone would do that?

It turns out it has to do with and being implemented as a macro, so if we look what’s the actual Clojure code being emitted the bytecode makes sense

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

The and__3941__auto__ variable which is the result of the first condition is being checked twice,

I guess this is the reason the temporary variable exists in the first place,

to avoid computation of the boolean expression twice and just checking for the result of it again.

If case the compiler analyzed the and as part of the if it could have emitted the result directly instead of

using a temporary variable and that nasty double check.

The Clojure case

Many of the different strategies explored previously apply if you want to decompile just about anything from bytecode (or machine language).

Since in our case we already know we’re decompiling Clojure, there are a lot of special cases we know we will never encounter.

Targeting our decompiler to only one language makes things easier, since while we’re not only supporting only one compiler, but we know we’ll never encounter manually generated bytecode, unless your using an agent or custom loader that has patched the bytecode, of course.

What’s next

In the next post I will show you two things, how to synchronize the decompiled bytecode tree with Clojure source code, and how to patch the debuggee on runtime to use our s-expression references using BCEL.

Much of the code to accomplish this was developed while understanding the problem, so it’s not open sourced yet, I’m planning to move stuff around and make it public, but if you want to look at the current mess just ping me, I’ll send it to you(you’ll need to un-rust your graph mangling skills tough).

Meanwhile, I’m guilespi on Twitter.